Swallowed Foreign Bodies that have Cardiac Complications in Children

William E Novotny and Cynthia P Keel

DOI10.36648/2471-805X.7.1.64

William E Novotny1* and Cynthia P Keel2

1 East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, Moye Boulevard, Greenville, North Carolina, USA

2 Vidant Medical Center, Maynard Children’s Hospital, Stantonsburg Road, Greenville, North Carolina, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- William E Novotny

East Carolina University,

Brody School of Medicine,

600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville,

North Carolina, USA-27834,

Tel: +252-744-8279;

E-mail: novotnyw@ecu.edu

Received Date: January 14, 2021; Accepted Date: January 28, 2021;Published Date: February 04, 2021

Citation: Novotny EW, Keel PC (2021) Swallowed Foreign Bodies that have Cardiac Complications in Children. Pediatric Care Vol.7 No.1: 5

Abstract

Swallowed foreign bodies are not uncommon occurrences in young children. The close proximity of the heart to the lower esophagus predisposes the heart and surrounding tissues to injury. Complications include accumulation of blood or air in the pericardial space and perforation through the myocardial wall with development of endocarditis. The inability of children to describe a history of ingestion or related symptoms makes timely diagnosis and treatment challenging. Prompt diagnosis and removal of sharp objects or button batteries may help to avoid esophageal penetration and subsequent cardiac complications. Radio- opaque foreign bodies are often readily identified by plain radiographs but transthoracic sonography of the lower esophagus is an emerging technique for other objects.

Keywords

Esophagus; Foreign body; Pneumopericardium; Hemopericardium; Endocarditis; Children

Description

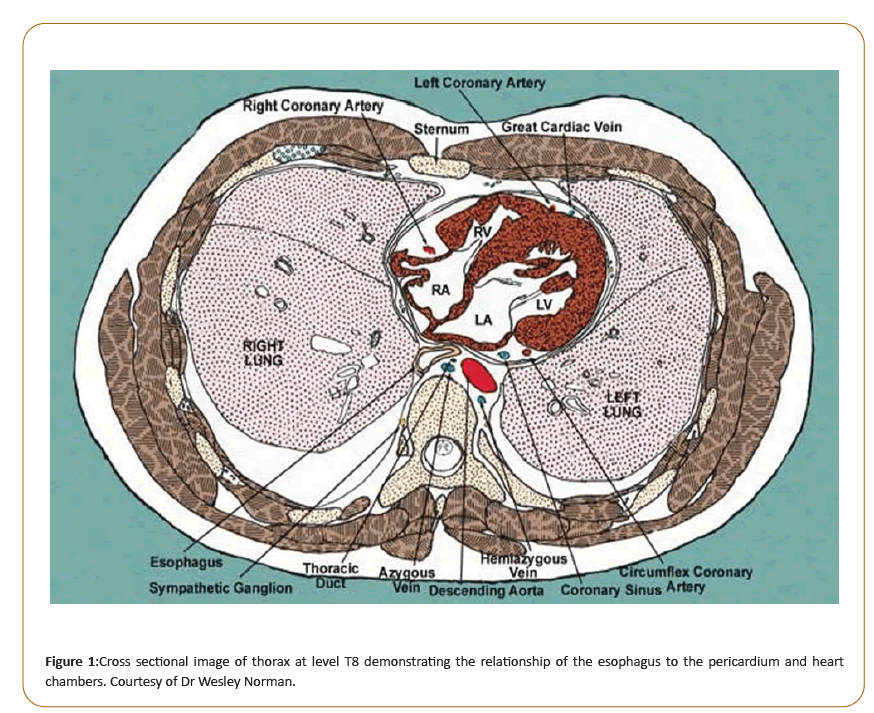

When a foreign Body (FB) is swallowed it may lodge in the thoracic esophagus. The lower third of the esophagus is located in close proximity to the atria of the heart (Figure 1). Rare but life-threatening infections and/or hemodynamic complications may develop. These include pericarditis and/or endocarditis associated with isolation of unusual organisms [1]. Young children may manifest recurrent febrile illness, impaired appetite or non-descript constitutional symptoms but are frequently unable to provide descriptive information that might be helpful in making a timely diagnosis. The onset of pain, localization of pain to oropharynx, chest or abdomen or the onset of dysphasia, each relative to the time of FB ingestion is lacking. An Esophageal Foreign Body (EFB) may cause inflammation, infection or bleeding when it erodes through the esophagus, penetrates the pericardial sac or migrates further through to the myocardial surface or even progresses into the heart chambers.

Seventy-five percent of foreign bodies ingested occur in children ≤ 5 years of age as reported by the American Association of Poison Control Centers in 2000 [2]. As compared to adults, swallowed FBs are predisposed to occur in children; they explore with their mouth, do not differentiate edible and inedible objects, lack molars that aid in chewing effectively, and are distracted while eating. Adults report dysphagia, persistence of abnormal sensation, blood stained saliva, history of choking or gagging with meals whereas children may simply refuse feeds, salivate, appear to have pain with swallowing or vomit repeatedly [3].

A child’s oropharynx, narrowed by the tongue and pharyngeal tonsils, may arrest movement of FBs into the esophagus, but not always. FBs that do progress into the esophagus typically pass through the gastrointestinal tract 80% to 90% of the time; 10% to 20% need non-operative intervention and approximately 1% require surgical intervention. An ingested FB that does progress to the esophagus will cause impaction, obstruction or perforation particularly near areas of anatomic narrowing: the upper esophageal sphincter, the aortic arch/left mainstem bronchus or the lower esophageal sphincter. In a study of both adults and children, esophageal FBs lodge in the cervical esophagus just below the cricopharyngeous in 75.9% of 1224 cases and lower esophagus in 0.65% of cases [3].

Probably less than 1% of ingested FBs cause perforation but when sharp pointed FBs are considered, up to 35% incidence of perforation can occur [4]. In adults, EFBs cause esophageal wall penetration/perforation in only 1% to 4% of cases; in contrast, however, sharp, elongated fish bone EFBs penetrate the esophagus in >50% of cases [5]. In Asian children, fish bones have routinely been noted to be most common ingested sharp foreign body due to a diet that is rich in fish. Fortunately most fish bones impact in tissues above or at the beginning of the upper esophagus. In a 1993 prospective study of 244 children in the United States with FB ingestions sharp objects comprised 10% of all FB ingestions [2]. The most common sharp objects ingested included straight pins, safety pins, bristles and pine needles. From 1995-2015 in the USA 6.3% of 759,074 suspected or confirmed FB ingestions in children <6 years of age included nails, screws, tacks or bolts [6]. Depending on FB composition, plain radiographs obtained for diagnostic purposes were revealing for metal (100% of cases), glass (43% of cases), fish bones (26% of cases) and wood (0% of cases) [2].

Smooth-edged ingested EFBs include coins, small balls and button batteries. When esophageal perforation occurs purported mechanisms include a combination of local inflammation and prolonged direct pressure necrosis. Coined shaped button batteries more rapidly cause visible tissue damage. Within 15 minutes of direct tissue contact flow of electrical current at the negative pole of the battery generates hydroxide through hydrolysis. The resultant highly alkaline environment of the surrounding tissues results in liquefaction necrosis. A window for injury-free battery removal is less than 2 hours [7]. An anterior- posterior chest radiograph demonstrates a coin shape with a double ring or halo. The narrow side of the battery is the site at which hydroxide is generated. An anterior-posterior chest radiograph demonstrates a coin shaped object with a double ring or halo; the negative pole of the battery is represented as the inner ring. Importantly, on the lateral chest radiograph, the negative pole narrower diameter protrude is of immense concern when it is situated ventrally in the direction of the esophagus and heart [7].

The thoracic esophagus lacks a serosal covering thus increasing its vulnerability to perforation by ingested and impacted foreign bodies. Major components of the central cardiovascular system are situated near the thoracic esophagus. The upper esophagus is adjacent to the aorta at the level of the third thoracic vertebra and the atria of the heart are located in direct apposition toe the eleventh thoracic vertebra (Figure 1). The close proximity of these structures makes them accessible to eroding or migrating EFBs.

Esophageal perforations due to foreign body impaction were reported to occur in 5 of 7 children in the thoracic esophagus (not cervical esophagus) [8]. Esophageal pericardial fistulas can develop from the erosion of EFBs ventrally. Esophageal perforations have been reported to be associated with coexistence of pericarditis in 12.5% of one small series of 24 adults [9]. Erosion of sharp FBs through the lower esophagus into the pericardial space and into the heart may cause pericarditis with pus or fluid accumulation in the pericardial cavity [1, 10-13]. Hemopericardium may also be caused by ingestion of safety pins, or fish bones with excoriation of the epicardium frequently visualized. Tamponade has been associated with the occurrence of hemopericardium [14,15]. Ingested FBs also can penetrate through the myocardium and into the chambers of the heart. Ingested straw or bristles have been reported in children four times to have migrated from the esophageal lumen and to penetrate the right heart. In each case coexisted endocarditis of the tricuspid valve apparatus occurred [1,15-18]. In each case the diagnosis was delayed.

Button batteries impacted in the esophagus can damage the esophageal wall and injure deeper tissues. A 3-year-old child with an impacted button battery in the lower esophagus developed a EPF that was associated with a pneumopericardium [19].

Recently, sonography has been used to detect esophageal foreign bodies in children [20]. This modality can evaluate the cervical and thoracic esophagus, including the gastroesophageal junction. This has the obvious advantages of rapid bedside evaluation and avoidance of radiation exposure.

Discussion and Conclusion

Young children are a special risk for frequent ingestion of FBs which may be associated with esophageal perforation and pericarditis. Sharp FBs can penetrate the ventral esophageal wall, abrade the epicardium and cause hemopericardium with associated cardiac tamponade. Objects penetrating the atria of the heart can initiate endocarditis. Radiolucent EFBs may be more readily and rapidly detected ultrasound. An ingested button battery with narrow side directed ventrally may quickly injure the esophageal wall and deeper tissue; button batteries have potential to produce cardiac complications.

References

- Novotny WE, Keel CP. Why humans should not eat broom straws: Pericarditis and endocarditis. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2020; 13:144-146

- Kramer RE, Lerner DG, Lin T, Manfredi M, Shah M, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: A clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. JPGN 2015;60:562-574

- Nandi P, Ong GB. Foreign body in the oesophagus: Review 2394 cases.Br J Surg 1978;65:5-9.

- Vizcarrondo FJ, Brady PG, Nord HJ. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1983;29:208-210

- Kim HU. Oroesophageal fish bone foreign body. Cliin Endosc 2016;49:318-326

- Orsagh-Yentis D, McAdams RJ, Roberts KJ, McKenzie L. Foreign-body ingestions ofyoung children treated in US emergency departments: 1995-2015. Pediatrics 2019;143(5):e20181988

- Hoagland MA, Ing RJ, Jatana KR, Jacobs IN, Chatterjee D. Anesthetic implications of the new guidelines for button battery ingestion in children. Pediatric Anesthesiology 2020;130:665-672

- Peters NJ, Mahajan JK, Bawa M, Chabbra A, Garg R. Esophageal perforations due to foreign body impaction in children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2015;50:1260-1263

- Hankins JR, McLaughlin JS. Pericarditis with effusion complicating esophageal perforation. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 1976;73:225-229.

- Erdal U, Mehmet D, Turkay K, Mehmet IA, Ibrahim N, Hasan B. Esophageal perforation and myocardial penetration caused by swallowing a foreign body leading to a misdiagnosis of acute coronary syndrome: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2015;9:57

- Choi JB, Lee SY, Jeong JW. Delayed diagnosis of purulent pericarditis caused by esophagopericardial fistula by computed tomography scan and echocardiography. European Journal of Cardio-thoracic Surgery 2001;20:1267-1269

- Duman H, Bakirci EM, Karadag Z, Ugurlu Y. Esophageal rupture complicated by acute pericarditis. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 2014;42:658-661.

- Kim Th, Kim SW, Seo GS, Choi SC, Nah Y. Pyopneumocardium due to an esophagopericardial fistula with a fish bone. AJG 2003;98:1441-2

- Sugunan S, Krishnan, AS, Devakumar, Arif AK. Safety-pin induced hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade in an infant. Indian Pediatrics. 2018;55:521-522.

- Sharland MG, McCaughan BC. Perforation of the esophagus by a fish bone leading to cardiac tamponade. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:969-71

- Johnson DH, Rosenthal A, Nadas AS. A forty-year review of bacterial endocarditis in infancy and childhood. Circulation 1975;51:581-588.

- Farber S, Craig JM. Clinical pathological conference . J of Pediatrics 1956;49:330-341.

- Hiller EJ. Bristle in the heart. British Medical Journal 1968;4:812.

- Soni JP, Choudhary S, Sharma P, Makwana M. Pneumopericardium due to ingestion of button battery. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2016;9:94-5

- Mori T, Nomura O, Hagiwara Y. Another useful application of point-of-care ultrasound: Detection of esophageal foreign bodies in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care 2019;35:154-156

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences