Meta-analysis of the Relationship between Life Events and Depression in Adolescents

Li Yue, Zhang Dajun, Liang Yinghao and Hu Tianqiang

DOI10.21767/2471-805X.100008

Li Yue, Zhang Dajun*, Liang Yinghao and Hu Tianqiang

Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Zhang dajun

Southwest University, Chongqing, China.

Tel: +8613509495486

E-mail: zhangdj@swu.edu.cn

Received date: December 14, 2015; Accepted: January 29, 2016; Published date: February 06,2016

Citation: Li Yue, Dajun Z, Yinghao L, et al. Metaanalysis of the Relationship between Life Events and Depression in Adolescents. J Pediatr Care.2016, 2:1. doi:10.21767/2471-805X.100008

Abstract

In the present study, a meta-analysis of 71 independent samples was performed to assess the relationship between life events and adolescent depression. In ddition, the influence of correlated variables is discussed. Analysis using the fixedeffect model showed that life events are positively correlated with adolescent depression (r = 0.319). Gender, cultural background, and type of life event might mediate the relationship between life events and adolescent depression: the relationship between depression and life events was greater in adolescent females than in adolescent males. Compared to adolescents in Western countries, life events more heavily affected depression in adolescents in China. Trivial affairs were more related to adolescent depression than were critical life events. Moreover, the way in which life events were measured did not affect the observed relationship between life events and depression. Thus, the following conclusions were reached: life events are closely related to adolescent depression, and the relationship between the two is affected by gender, cultural background, and type of life event. The measurement of daily events does not affect the relationship between life events and depression in adolescents.

https://tipobette.com https://vdcasinoyagiris.com https://venusbetting.com https://sahabetting.com https://sekabete.com https://sahabete-giris.com https://onwine-giris.com https://matadorbet-giris.com https://casibomkayit.com https://casibomba.com https://casiboms.com https://casinoplusa.org https://casibomlink.com https://yenicasibom.com https://jojobetegiris.com https://jojoguncel.com https://jojobetyeni.com https://girisgrandbetting.com https://pashabetegiris.com https://grandbettingyeni.com

Keywords

Life events; Depression; Meta-analysis; Juvenile

Introduction

The influence of life events on psychological health has been extensively studied. Several such studies show that life events are associated with juvenile depression [1-5]. Negative life events may significantly influence the development of depressive mood, and depressive mood can, in turn, negatively affect one’s life; thus, a vicious cycle may emerge that can damage one’s mental health. Depression normally starts in adolescence and later becomes one of the important causes for mental illness. The prevalence rate of juvenile depression has been increasing in recent years, while the age of onset has been decreasing [6]. Thus, assessing the relationship between life events and juvenile depression is of great significance to the development of adolescent mental health interventions.

Research shows that the most typical age-related characteristics of juveniles are stable emotionality, gradually maturing psychology, and social development through active participation in social experience and practice. In one study [7], the term “extended adolescence” was used to describe 18- to 25-year-olds in industrialized countries who have delayed social developments due to higher education. In the present study, juveniles are defined as individuals aged 11 to 25 years [8].

Although the correlation between life events and juvenile depression has been demonstrated, the noted relationship between these factors varies across studies: correlation coefficients are as high as 0.587 and 0.49 in Pengli et al. [2] and Fox et al. [9], respectively, and as low as 0.09 and 0.04 in Boardman et al. [3] and Wadsworth et al. [10], respectively. To establish a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the relationship between life events and juvenile depression, the present study performed a meta-analysis on nearly ten years of Chinese and English empirical research. Moderating variables were considered to determine whether gender, cultural background, or type and measurement method of life events affected the relationship between juvenile life events and depression.

Literature Review and Theoretical Hypothesis

Literature review

Life events: The concept that life events can affect depression derives from studies on stress. Modern studies generally adopt the Lazarus and Folkman [11] perspective that stress is the product of one’s evaluation of stimuli and responses; in other words, cognitive processes determine stress. Cognitive processes include thoughts pertaining to interactions between stressful events (e.g., personal and environmental requirements), intervention factors (e.g., personal and environmental resources), and stress reactions (e.g., physical and mental health). It is widely recognized by stress researchers in the psychology field that stress is a kind of cognitive process. In order to figure out which life change causes the highest stress, Holmes [12] introduces a new concept called “life events”, life events are those life changes that affecting human psychology. According to this perspective, both positive and negative events can induce stress in individuals. However, later studies indicated that not all life events lead to stress. The key determinant in whether an individual perceives an event as stressful is the degree to which the event threatens his or her self-esteem and security, and whether he or she has sufficient resources to combat the adverse effects of the event. Further, it has been demonstrated that only negative life events influence mental health [13-15].

There are two general perspectives regarding the classification of life events. In the first, life events are classified as major events or daily hassles based on the length of stress period, which is longer for daily hassles and shorter for major life events. Stress resulting from traumatic major life events is uncontrollable and unpredictable. By contrast, stress from daily hassles is more durable and has a cumulative effect on the individual's physical and mental health; however, this effect is much weaker than that of traumatic events [16,17]. In the second perspective, life events are classified as positive or negative based on their qualitative nature. Positive life events, such as marriage or winning an award, are active events for the individual and typically result in a pleasant emotional experience, which facilitates positive emotions. Negative life events, such as relationship dissolution, illness, and death, are associated with a passive emotional experience that negatively influences one’s physical and mental health. The studies examined in the present analysis primarily pertain to negative life events that induce negative emotions and require substantial adaptation efforts and social readjustments.

Holmes and Rahe were the first to quantitatively evaluate life events. They developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), which lists common stressful life events in American daily life and the degree of readjustment required for each event, which is referred to as the Life Change Unite (LCU). Following this, the Life Events Scale (LES) was developed based on the SRRS. Since then, quantitative studies on life events have been gradually increasing through the use of well-known life events scales like the Interviews of Recent Life Events (IRLE) and the Student-Life Stress Inventory (SLSI), which are mainly applied in Western cultures in different living environments.

In addition, the Stressful Life Events Rating Scale [18], the Life Event Scale by Yang Delin and Zhang Yalin [14], and the Life Event Scale by Zhang Mingyuan [19] are used to assess respondents’ positive and negative life events within the domains of family, work, and interpersonal relationships. The Life Events Scale of High school and College Students [20] includes life events that pertain to interpersonal relationships, economic conditions, capability, and health. The Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Check List (ASLEC) [21] is limited to negative life events in the domains of academic pressure, interpersonal relationships, health adaptation, punishment, loss, and others. The Freshman Life Events Questionnaire developed by Chang Fengjing [22] has also been used in domestic studies. Thus, the abovementioned scales are suitable for use in a Chinese population.

As the present study is a meta-analysis, we included studies that applied self-designed scales to measure life events, which focus on measuring frequency of occurrence and subjective perception of life events [23-25], such as the SRRS, LES, and ASLEC; in addition, several self-designed scales solely assess frequency of occurrence [26,27].

Depression: Angold [28] states that depression is characterized by the following: unhappiness, sadness or mental pain, depressive reactions to adverse situations or events, fluctuations from a normal state to depressed mood, and the lack of long-lasting and stable pleasant mood.

Depression can be divided into depressive mood, depressive syndromes, or depressive disorder according to exhibited characteristics, judgment standards, and the degree to which the symptoms interfere with the individual’s life. Depressive mood refers to feelings of unhappiness or sadness; depressive syndromes refer to the presence of multiple depression symptoms, including unhappiness, low self-esteem, anxiety, pessimism, guilt, and loneliness. Diagnosis of depressive disorder should be based on clinical diagnostic criteria for emotions, behaviors, cognitions, somatic symptoms, and related dysfunctions, and assessed via structured clinical interviews and observations. Specific features of depressive disorder include depression, loss of interest, sadness, changes in appetite, somatic complaints (such as pain), changes in mental activity (e.g., loss of excitement), fatigue, a sense of meaninglessness or guilt, attention deficits, and suicidal ideation [29,30] In the present study, depressive mood refers to individuals’ subjective feelings of depression. Based on the definitions of juvenile depression from Feng Zhengzhi and Zhang Dajun [31], depressive mood is a significant and lasting feeling of sorrow, misfortune, or irritability that primarily manifests as melancholy.

Depressive mood is one of the most common psychological problems in juveniles [30]. Depressive mood primarily consists of the following 4 groups of characteristics: (1) pessimism, sadness, disappointment, helplessness, indifference, or despair; (2) negative self-concept and self-evaluation, reduced selfconfidence, a sense of that one is useless and inferior, self-guilt, and suicidal ideation; (3) sleep disturbances, hypoactivity in appetite, sex, and interest; and (4) decreased activity levels and withdrawal from social interaction.

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) is the earliest and most widely applied children's depression measurement scale. Adapted from the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Children's Depression Inventory was the first scale used to measure depressive mood in children and adolescents in Western countries. The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), developed by Radloff from the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 1977, is also widely used for screening depressive symptoms in the general population. It is not only suitable for its original target (adults), but is appropriate for use in adolescents and elderly people. The Depression Scale from the Symptom Checklist-90, as well as its simplified version, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), is also widely used self-rating depression scales. In addition, the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) established by Zung is commonly used.

In the measurement of juvenile depression in China, Chinese versions of foreign depression scales such as the SCL-90, SDS, and CES-D are used. The Middle School Student Mental Health Scale established by Jisheng [32] is designed to assess depression in Chinese adolescents.

Relationship between life events and depression: Life events and depression are closely related. First, life events influence the development of juvenile depression. Zhang Yuejuan et al. [33] shows that depressive mood in college students is related to negative life events, negative automatic thoughts, and negative response styles. Li Li [34] also found significant differences in life events between depressed juveniles and healthy juveniles, and that adolescents exhibiting depressive symptoms encounter more negative life events. In a summary of the relationship between life events and depression, Liu Xiaohua [35] concluded the following: First, 92% of individuals experienced negative life events prior to the onset of depression, which suggests that life events are a key factor in depression; events that entail loss and humiliation are more likely to trigger depression. Second, life events not only influence the onset and symptoms of depression, but also influence its recurrence. Finally, different types of life events have different influences on the onset, improvement, and stability of depression. Regarding the relationship between life events and depression, it is estimated that roughly 75% of stressful life events can contribute to the onset of depression. This relationship is closer for the first incidence of depression than for recurrence. Early international research has also demonstrated an association between life events and juvenile depression [36,37].

Second, depressive mood can also predict life events. Williamson’s [38] results indicate that depressed adolescents are more likely to experience dependent life events than are normal individuals. In a longitudinal study [39], it was found that the depression, anxiety, and neuroticism of juveniles (especially girls) predicts life events. Carlin and Bowes also found that among community juvenile groups in one city of Australia, individuals with depression and anxiety tended to experience more negative life events.

Theoretical Assumptions

Main effects of life events on juvenile depression

Life events influence students' mental health, and represent an important index for quantifying psychological pressure [21]. Life events and depression significantly increase in adolescence. Many studies have attempted to determine the extent to which life events affect juvenile depression, with results showing that adolescents of various cultural backgrounds are impacted by life events; however, the degree to which they are affected may differ.

Most studies show that the occurrence and development of depression are closely related to life events. When analyzing the correlation between depression, anxiety, and stressors, Yu Jie et al. [40] found that depression in rural middle school students is closely related to negative life events, mainly those pertaining to interpersonal relationships, academic pressure, and punishment. Xu Biyun et al. [39] showed that juvenile life events are closely related to behavioral and emotional problems [41]. Zhou Pingyan’s [42] comprehensive study on the influencing factors of depression at home and abroad showed that life events play in important role in depression. The relationship between life events and depression has been demonstrated in domestic and international studies conducted from the 1970s to the 1990s [38,43-51]. For example, Shrout's [51] research shows that the probability of experiencing a significant, negative life event is 2.5 times higher in depressed individuals than in non-depressed individuals. Kendler’s [48] study showed that, in females, there are 13 kinds of life events that significantly predict the onset of depression, and 4 of these had a relative odds ratio > 10 for predicting depression. However, other studies [52,53] did not find a significant relationship between life events and depression. In the present study, Hypothesis 1 is based on the results of many previous studies that indicated a significant positive correlation between juvenile life events and depression.

Regulatory effects of related factors on the relationship between juvenile life event and depression

The observed correlation between juvenile life events and depression has varied across studies, which might have resulted from differences in participant and experimental characteristics such as gender, cultural background, and measurement method. Differences in the types of life events participants experienced may have also influenced the observed relationship between life events and depression. Therefore, it is necessary to measure other factors that may contribute to the relationship between juvenile life events and depression.

Gender: Studies have indicated that the prevalence rate of depression significantly increases in adolescence, and that the incidence of depression varies as a function of gender. Depression is more likely to be detected in girls than boys, and this trend continues into adulthood [51]. Further, gender differences in depression are trans-regional and trans-cultural [54]. In Kessler and Walters’ [55] study of 15 to 24-year-olds, the depression rate was 16.1% for girls and 9% for boys. In addition, Veytia López et al. [56] showed that juvenile girls experience more negative life events and have a greater incidence of depression. Sherrill et al. [57] found that females with depression experience a greater number of negative life events than do their male counterparts; moreover, such a gender difference does not exist in nondepressed individuals. Maciejewski et al. [58] found that the rate of depression following a stressful life event is almost three times higher in females than in males. However, Kendler et al. [59] showed that most stressful life events have similar effects on both males and females, and they concluded that life events do not account for gender differences in depression rates. In order to determine whether gender affects the relationship between life events and depression in adolescents, gender was included as a controlling variable in the present meta-analysis. It was hypothesized that gender influences the relationship between life events and depression in adolescents (Hypothesis 2). Moreover, it was hypothesized that the correlation between juvenile life events and depression would be higher in females than in males.

Cultural background: In the present study, “cultural background” mainly refers to the Chinese cultural background and the Western cultural background of America, Canada, Norway, and other countries. Culture has a profound and imperceptible impact on social development and personal growth. Culture affects individuals’ cognition and mode of thinking [60]. The psychological constructions of attitude, value, belief, and regulation contained in culture affect individuals’ responses to life events and selection of coping strategies. Given that they are in a crucial period in the formation of their attitudes and values, adolescents are greatly influenced by culture. Thus, culture may mediate the relationship between life events and depression in adolescents.

Studies included in this meta-analysis show that the relationship between life events and depression in adolescence is closer in adolescents of an Eastern cultural background (r = 0.04–0.56) than in adolescents of a Western cultural background (r = 0.13- 0.587). Thus, Hypothesis 3 proposes that the correlation between life events and depression will be higher for adolescents of an eastern Chinese cultural background relative to adolescents of a Western cultural background.

Types of life events: Types of life events include major events and daily hassles, which are believed by most researchers to affect juvenile depression [11]. Several studies have examined whether these two classes of life events differentially influence depression risk. Some studies suggest that major events have a greater association with depression than do daily hassles [61]. On the contrary, Windle and Windle [62] showed that major events and daily hassles do not differ in the extent to which they predict emotional and behavioral problems. However, most studies found that daily hassles are more closely related to juvenile depression than are major events [63-66]. Kanner et al. [13] stated that daily hassles are more predictive of juvenile emotional problems than are major events. Based on the results of a cross-lagged analysis of life events and depression in college students, Li Yongxin et al. [65] concluded that daily hassles, but not major events, significantly predict depression. Thus, Hypothesis 4 states that compared to major events, daily hassles are more closely related to juvenile depression.

Measuring methods of life events: According to Holmes’ [12] theory of life events, a life event can be measured by its subjective frequency and degree of subjiective feeling. Most studies included in the present meta-analysis measured frequency and degree of objective perception [53,67-70]. However, only frequency of life events was measured in other included studies [25,29,54,71,72]. Is it possible that this difference in measurement influences the observed relationship between life events and depression in adolescence? Measurement of frequency and degree of perception is performed to determine the quantity and nature of life events; however, neither method is indispensable [12]. The cognitive evaluation model of stress holds that that the stress response is directly proportional to an individual’s cognitive evaluation of a given situation or event. This cognitive evaluation essentially determines the occurrence and degree of the stress response. Therefore, it is necessary to measure individuals’ experience of life events. Measuring the frequency of life events may not yield an adequate understanding of the way in which life events affect people. Indeed, the frequency of a given life event is subjective, while depression is a type of emotional problem. Thus, in addition to measuring frequency, it is necessary to assess juveniles’ subjective feelings about life events. The studies included in the meta-analysis show that there is no difference in results between studies testing just the frequency of life events (r = 0.05-0.56) and those testing frequency and degree of perception simultaneously (r = 0.04-0.587). While contradictions between theory and data prevent us from making clear assumptions, we will measure measuring methods of life events as a moderating variable in an attempt to assess whether it affects the relationship between life events and depression in adolescents.

Research Methodology

Data collection

Both Chinese and English studies were included in this metaanalysis. The primary sources used to obtain Chinese studies were the CNKI database (China Journal Net), the China Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP Journal), and the Wanfang data retrieval system. “Life events,” “adolescent,” “depression,” and “mental health” were used as search keywords. Since the use of “adolescent” as a key word yielded many studies of college students, college students were included in our age range. The main sources used to locate English studies were Science Direct, Web of Science, Springer Link, and Google Scholar, while Medalink was used as a supplementary source. Studies without a full text were obtained directly from the author or by virtue of interlibrary loan. English terms such as “life events,” depression,” “adolescent,” “mental health,” and “adaption” were used as key words. The selected studies were screened according to the following standards: (1) The study explored the relationship between life events and adolescent depression; (2) a correlation between these two variables was reported, excluding data obtained through structural equation modeling, regression analysis, and other statistical methods; (3) it was not a duplicate study; and (4) subjects were normal adolescents who had not been diagnosed with any physical or emotional illness. Given that the life events to which adolescents are exposed have changed with the recent and rapid social development, studies conducted more than a decade ago were excluded from the meta-analysis.

A total of 65 studies were eventually incorporated into the metaanalysis: 43 Chinese studies and 22 English studies, of which 55 were academic papers and 10 dissertations. Seventy-one independent samples and effect sizes were obtained, and the total number of subjects was 37,173.

Literature coding

The literature coding standards were as follows. (1) Effect sizes were in the unit of independent samples. When several independent samples were included in a study, each was coded separately. In cases where the same study was conducted at different times with samples of various sizes, each sample was coded separately. (2) When the relationship between different types of life events and adolescent depression, rather than a population correlation, was reported in literature, the effect size was based on the mean of each dimension. (3) The first two standards concern the main effects of life events on adolescent depression. For the moderating effect of gender, studies were coded according to whether all the subjects were female or male. For the moderating effect of cultural background, studies were coded according to whether 85% subjects are of a Chinese or Western cultural background. For the moderating effect of type of life events, studies were grouped according to whether the correlation between major events and/or trivial affairs was reported. Finally, for the moderating effect of measurement type, studies were grouped according to whether the study assessed both frequency and subjective intensity of life events, or frequency alone.

Statistical analysis method

Data analysis was conducted via the professional meta-analysis software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2.0 (CMA 2.0). CMA 2.0 is special meta-analysis software developed and updated by the International Cochrane Collaboration Center. Effect size (r) refers to a single correlation coefficient or an averaged correlation coefficient across several samples, as mentioned above CMA2.0 allows for the generation of analysis results for both a fixed model and a random model. A fixed effect model was adopted in this study. The major difference between the fixed model and the random model is that different elements are used to compute the weights. The within-study variation was used to calculate weights in the fixed model, while the within and between-study variation was used in the random model. The fixed effect model assumes that there is only one real effect size that applies to all studies included in the meta-analysis, and it is more accurate than is the random effect model in estimating the relationship between two related variables.

Results

Publication bias test and effect size homogeneity test of the relationship between life events and adolescent depression

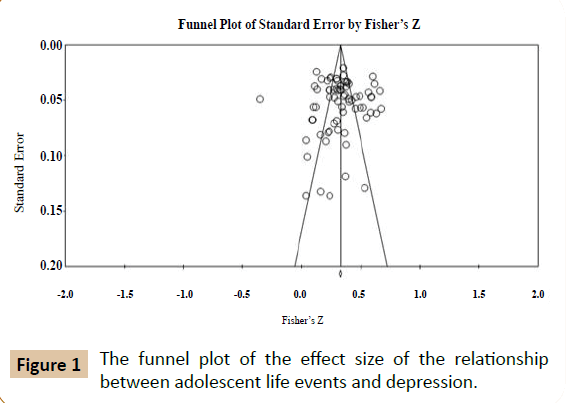

Publication bias is inevitable in meta-analysis; thus, it is necessary to test for publication bias because of its direct influence on the analysis results. Figure 1 shows the funnel plot of the effect size of the relationship between adolescent life events and depression. The horizontal axis in Figure 1 is Fisher’s Z effect size, while the vertical axis is the standard deviation of Fisher’s Z effect size. As can be seen in Figure 1, most studies are at the top of the funnel and distributed near the average effect size. Moreover, the fail-safe number is 5577 > 5K + 10 (K refers to the quantity of effect sizes), indicating that another 5577 studies are needed to perform an adequate reassessment. Thus, the results of this meta-analysis can be perceived as reliable (Figure 1).

A homogeneity test (Q-test) is used to examine whether each study result can represent the sample estimation of all effect sizes. Q-test results are employed to examine whether differences among independent samples’ effect sizes are caused by potential moderating variables. If the results are significant (QBET >.05), the role of the moderating variables is assessed in a post-test. Table 1 shows the test results for effect size homogeneity. The Q-statistics indicate that the effect size is 969.029 (p < 0.001), which indicates heterogeneity between studies. As this may have resulted from the role of moderating variables, the moderating effect of the related variables is also discussed in this study (Table 1).

| Model | k | Heterogeneity | Tau-squared | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | 71 | Q-value | df (Q) | I2 | Tau2 | SE | Variance | Tau | |

| 969.029 | 70 | <0.001 | 92.776 | 0.024 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.156 | ||

Table 1: The test results for effect size homogeneity.

Test of main effects

Table 2 presents the demographic information of the studies used in the meta-analysis, while Table 3 shows the fixed model analysis results of the relationship between life events and adolescent depression. As can be seen from Table 3, there is a positive correlation between adolescent life events and depression (r = 0.319, p < 0.01). According to Cohen, an effect size is small if it is less than or equal to 0.1, moderate if it is around 0.25, and large if it is larger than or equal to 0.40. Thus, consistent with Hypothesis 1, there is a positive correlation between life events and adolescent depression (Tables 2 and 3).

| Source | N | Mean age | %female | Cultural background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu Pengliet al. [2] | 303 | 20 | 50.83 | Chinese |

| He Xinshe [68] | 580 | Chinese | ||

| Zhou Kehuiet al.[135] | 453 | 20 | 38.63 | Chinese |

| Li Yongxin [106] | 234 | 18.91 | 64.96 | Chinese |

| Wang Fang [74] | 388 | 16.39 | 59.80 | Chinese |

| Li Yi [105] | 612 | 21 | 83.17 | Chinese |

| Chen Huiet al. [75] | 710 | 43.66 | Chinese | |

| Zhang Tingting[52] | 419 | 21 | 52.74 | Chinese |

| Zhang Yuejuan[33] | 321 | 20.53 | 54.51 | Chinese |

| Chen Xiumei[73] | 1222 | 52.29 | Chinese | |

| Wei Yimei,Zhang Jian[67] | 811 | 48.95 | Chinese | |

| Xi Qiaozhen [87] | 313 | 54.31 | Chinese | |

| Chen Fuxiaet al.[111] | 138 | 13.04 | Chinese | |

| Liu Jiananet al.[109] | 422 | 17.52 | Chinese | |

| Li Shaoming [102] | 384 | Chinese | ||

| DebngHoucaiet al.[115] | 620 | 46.13 | Chinese | |

| Dai Chengshu [114] | 720 | Chinese | ||

| Liao Chuanjinget al. | 595 | 17.18 | 60.50 | Chinese |

| XueZhaoxiaet al.[131] | 155 | 18.87 | Chinese | |

| Li Yuxia [107] | 1180 | 15.46 | 54.41 | Chinese |

| Yang Li [66] | 454 | 18.51 | 35.68 | Chinese |

| Liu Baoling,GaoYueming [108] | 444 | 65.32 | Chinese | |

| Li Songying [103] | 202 | 55.94 | Chinese | |

| Tan Lieret al. | 601 | 20.6 | Chinese | |

| Li Yongxin, Zhou Guangya [106] | 270 | 18.84 | 62.59 | Chinese |

| Zhang Li, Liu Bo [132] | 215 | 19.5 | 100 | Chinese |

| Zhang Wenyue [133] | 950 | 21.5 | 64.52 | Chinese |

| Li Yanhong[104] | 126 | Chinese | ||

| Li Peng [70] | 545 | 57.06 | Chinese | |

| Wang Lien, Wang Jisheng [85] | 957 | 20 | 62.28 | Chinese |

| Ma Weina, XuHua [23] | 274 | 16.82 | 54.01 | Chinese |

| Wang Jun, Jin Yuelong [24] | 1687 | 19.66 | 54.71 | Chinese |

| Wang Xixiuet al. | 404 | Chinese | ||

| Yang Juan[72] | 618 | Chinese | ||

| Sheng Aiping [81] | 450 | 20.12 | 77.56 | Chinese |

| Chen Hongminet al.[112] | 468 | 57.91 | Chinese | |

| Deng Huijuan [79] | 304 | 30.92 | Chinese | |

| Chen Yu et al.[113] | 469 | 100 | Chinese | |

| Liu Ting et al.[110],study1 | 60 | 19.85 | 0 | Chinese |

| Liu Ting et al.[110],study2 | 57 | 19.85 | 0 | Chinese |

| Chen Chong ,XuLinyong | 732 | 20.42 | 50.68 | Chinese |

| Sun Shuronget al.[80] | 314 | Chinese | ||

| Xiao Jianwei, Shi Yong | 456 | 50.22 | Chinese | |

| Marcela Veytia[5] | 2292 | 17 | 54.01 | Western |

| Amy J Kercheret al.[25] | 896 | 12.3 | 100 | Western |

| Esther M.C. Boumaaet al. [136],study1 | 1100 | 13.6 | 100 | Western |

| Esther M.C. Boumaaet al.[136],study2 | 1049 | 13.6 | 0 | Western |

| Vivian Kraaijet al.[101] | 1310 | 18 | 55.73 | Western |

| Boardman et al.[3],study1 | 221 | Western | ||

| Boardman et al.[3],study2 | 221 | Western | ||

| Boardman et al.[3],study3 | 320 | Western | ||

| Boardman et al.[3],study4 | 320 | Western | ||

| eremy K. Fox et al.[9] | 63 | 17.5 | 100 | Western |

| eff M. Gauet al.[26] | 173 | 15.5 | 57.80 | Western |

| Golan Shaharet al. [27],study1 | 603 | 15 | 53.89 | Western |

| Golan Shaharet al.[27],study2 | 603 | 16 | 53.89 | Western |

| Emily Burton et al. [4] | 496 | 13 | 100 | Western |

| BRIT OPPEDA et al. | 633 | 47.23 | Western | |

| Martha E.Wadsworth et al.[10] | 57 | 14.5 | Western | |

| Susan Nolen-Hoeksema [54] | 1065 | 12.2 | 48.83 | Western |

| Andrea J. Romero | 881 | 13 | 45.74 | Western |

| Suzanne C. O et al. [53] | 135 | Western | ||

| Suzanne C. O’neillet al. [53] | 101 | 67.32 | Western | |

| Misaki N. Natsuakiet al. [95] | 897 | 11 | 53.51 | Western |

| Edward C. Changaet al.[22] | 263 | 15.73 | 61.98 | Western |

| Rachael Dyson and Kimberly Renk [116] | 74 | 18.47 | 68.92 | Western |

| Connecticut | 1065 | 48.83 | Western | |

| Megan Flynn and Karen D. Rudolph [71] | 167 | 12.41 | 51.50 | Western |

| Trine Waaktaaraet al. [84] | 163 | 13.8 | 31.90 | Western |

| Rebecca Morrison and Rory C. O’Connor [94] | 161 | 19.32 | 64.60 | Western |

| Lea Rood et al. [98] | 805 | 12.4 | 59.88 | Western |

Table 2: Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Outcome | k | N | R(95%CI) | Q | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The relationship between life events and adolescent depression. | 71 | 37173 | 0.319***(0.310,0.328) | 969.029*** | 92.776 |

k: number of studies, r correlation, CI confidence interval, Q and I2 heterogeneity statistics *** p<0.001

Table 3: The fixed model analysis results of the relationship between life events and adolescent depression.

Test of moderating effects

The regulatory effects of the moderating variables, including the subjects’ gender and cultural background, and the types and measurement modes of life events, were also examined in the meta-analysis. These results are shown in Table 4.

| Outcome | k | N | R (95%CI) | Q | I2 | Contrasta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 25.274*** | |||||

| male | 3 | 1166 | 0.168(0.111,0.223) | 0.272*** | 0.000 | |

| female | 5 | 3024 | 0.331***(0.298,0.362) | 25.344*** | 84.217 | |

| Cultural background | 6.765** | |||||

| Chinese | 43 | 21637 | 0.329***(0.317,0.341) | 739.525*** | 94.321 | |

| Western | 28 | 18283 | 0.305***(0.291,0.315) | 222.739*** | 87.878 | |

| Type of life events | 8.304** | |||||

| major events | 4 | 1192 | 0.396***(0.347,0.443) | 1.381 | 0.000 | |

| daily hassles | 6 | 2088 | 0.481***(0.447,0.513) | 25.831*** | 80.644 | |

| Measuring methods of life events | 2.242 | |||||

| both b | 39 | 19870 | 0.325***(0.313,0.338) | 645.333*** | 94.112 | |

| only c | 16 | 8461 | 0.343***(0.324,0.362) | 111.799*** | 86.583 |

k number of studies, r correlation, CI confidence interval, Q and I2 heterogeneity statistics

a Contrast between subsets of studies, noted in Q

b Measuring both the frequency of life events and juveniles’ subjective feelings about life events

c Measuring only the frequency of life events

* p < 0. 05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001

Table 4: The regulatory effects of the moderating variables, including the subjects’ gender and cultural background.

It can be seen from Table 4 that gender, cultural background, and type of life events are likely to affect the relationship between life events and depression in adolescents. Thus, the results support Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4. However, the way in which life events are measured does not affect the observed relationship between adolescent life events and depression.

Discussions and Conclusions

Discussion of main effects

Life events are one of the external risk factors that affect mental health, and negative life events tend to exacerbate depression in adolescents. The quantitative analysis of 65 domestic and foreign studies on the relationship between life events and adolescent depression show that there is a significant positive correlation between life events and adolescent depression (r = 0.319, k = 71, N = 37,173). This illustrates that life events are closely related to adolescent depression, which is consistent with the results of many previous studies [5,9,24,73-75]. Hypothesis 1 was supported.

The stress-sensitization model can be applied to explain the correlation between adolescent life events and depression. Negative life events lead to a decrease in an individual’s tolerance for future stressful events. Thus, when subsequent negative life events occur, an individual will struggle to cope with them, which may lead to depression [76-78].

Both direct and indirect relationships exist between life events and adolescent depression. Kendler et al. [22] found through discrete-time survival analysis and co-twin control analysis that both direct and indirect relations exist between dependent stressful life events and depression, while independent stressful life events may have a complete direct relationship with depression. Further, life events may affect depression through interactions with other factors, such as coping style and selfefficacy. Some studies show that individuals with a more positive coping style experience fewer negative life events and are less affected by the negative life events they do encounter [79-87]. Ma Weina et al. [22] conducted a path analysis of life events, selfefficacy, and depression. They revealed that life events directly affect depression and indirectly influence depression through self-efficacy. For people with different degrees of self-efficacy, the same life events will lead to different emotional reactions. People with low self-efficacy are more likely to experience strong negative emotions in response to stressful life events, thus leading to depression.

Discussion of regulatory effects

Gender: According to the meta-analysis results, there is a significant difference in the relationship between life events and adolescent depression among different gender groups. The correlation for females is significantly higher than that for males. This result is consistent with those of previous studies [88-90]. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. This gender discrepancy can be explained by the three models proposed by Nolen-Hoeksema [91]. Model 1 assumes that the causes of depression are consistent between males and females, but are more prevalent in adolescent females. External negative stimuli and personality are the main incentives of depression. During adolescence, females begin to adapt themselves to role changes, confront more negative events, and are more likely to make internal attributions [92-99].

Model 2 holds that the causes of female and male depression are different: Females attach more importance to interpersonal communication, whereas males pay more attention to athletic ability. Girls tend to define themselves based on their relationships with others, while boys are more likely to define themselves through competition and competence [100-110]. Given that female adolescents encounter more interpersonal communication life events, the overall relationship between life events and depression is greater in females. According to Model 3, females have more traits that are associated with depression,are more concerned about external stimuli, and are more liable to cope in a passive, pensive, and sentimental way [111-118]. Thus, they are more prone to depression after encountering an external negative stimulus [119-115]. The cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction theory states that a cognitive vulnerability will amplify the negative emotions that result from negative life events. Inappropriate coping strategies will then be employed, which will eventually lead to negative attributions and subsequent negative life events, thus entailing a vicious circle. The issue of whether different types of life events differentially affect depression in different gender groups should be examined in future studies on the relationship between life events and depression. In addition, further investigations are needed to explore whether females possess more depression-related traits that will make them more vulnerable to the negative effects of stressful life events.

Cultural background: The results of the meta-analysis show that the relationship between life events and adolescent depression differs across cultural backgrounds. The correlation between these two variables is greater for individuals of a Chinese cultural background, thus supporting Hypothesis 3.

The composition of life events varies greatly across different cultural backgrounds. In Chinese culture, personal value lies in individual contributions to families and groups rather than personal capability. For students, family responsibility is best demonstrated through extraordinary academic performance [116]. As parents have higher expectations and evaluations of children’s academic performance, life events such as academic pressure have a greater impact on Chinese adolescents. In Chinese society, attending school is an effective way to rise from poverty towards wealth. This social pressure stimulates Chinese adolescents to perform academically, which often leads to stress. Studies show that academic and cultural elements play an important role in those stressful events faced by Chinese adolescents [117]. Moreover, the rapid modernization of Chinese society has revised the original family roles and social support system. However, these elements may protect individuals when they encounter negative life events [118].

Some studies show that culture influences the way people establish intimate relationships, which is related to interpersonal stress [119]. Chinese culture is characterized by collectivism, convergent thinking, reserved expressions of feelings, obedience, and an emphasis on relationships with others; by contrast, Western culture advocates personality, self-consciousness, and a more open approach to emotional expression. In Chinese culture, social relations, roles, rules, and united groups are more important than individual performance. Rather, individuals are expected to adjust themselves to meet others’ desires and to work for the development of groups, organizations, public institutions, and the nation [120]. Given this, adolescents entrenched in Chinese culture are more sensitive than are their Western counterparts to stressful life events relevant to interpersonal communication.

Further, the formation of self-identity is an importance task for adolescents. Following the development of self-concept, adolescents attach great significance to others’ evaluations and self-esteem. In Chinese culture, individuals are expected to express their feelings in an implicit way. Thus, it is not that easy for individuals to obtain affirmation and appreciation from parents and teachers. As a consequence, individual self-esteem may be affected, and negative life events may ensue.

Cultural background should be taken into account in future studies on the relationship between life events and adolescent depression. For instance, both measurement scale selection and coping strategies may be influenced by cultural background.

Types of life events: The results of the meta-analysis indicate that trivial affairs play a greater role in adolescent depression than do major events, a finding that is consistent with those of many previous studies [13,59-62]. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported. The stress coefficient model states that trivial affairs consume individual energy and physical strength, giving rise to health problems in the long-term [61]. Impressive as they are, major events happen less frequently for the majority of adolescents. Although trivial affairs are less stressful than major events are, they are persistent and ubiquitous [57]. Therefore, relative to major events, trivial affairs affect adolescents to a far greater degree. The diathesis-stress theory also states that the stress of trivial affairs better predicts depression than does the stress of major events [121]. Hence, attention should be paid to the different effects of different types of life events on adolescent depression in future studies to enable the development of more effective psychological interventions and mental health education programs.

Measurement modes of life events: The meta-analysis results show that the relationship between adolescent life events and depression is not influenced by the method used to measure life events. That is, there is no significant difference between measuring both the frequency and perceived severity of life events, and measuring frequency alone.

Life events are measured via self-evaluation. Thus, individuals’ feelings may have been included in the measurement of life event frequency. Specifically, individuals may have forgotten some events as a result of unimpressive individual feelings. Thus, life events that were not associated with high emotionality may not have been included in the tally. On the contrary, events with high emotionality are less likely to be forgotten and are more likely to be reported. It can be seen that life event frequency and subjective feelings about the events are sometimes intertwined and not easily separated. Thus, it is suggested that both frequency and subjective feelings should be measured in future studies assessing life events.

Research significance and prospects: The present meta-analysis is of both theoretical and practical significance. In terms of theoretical research, the meta-analysis results not only provide the correlation coefficients for life events and adolescent depression, but also address the influence of several moderating variables on this relationship. In addition, the results have significance for future studies of life events. Regarding practical applications, studies show that life events exert a profound influence on adolescent depression. Since there is a significant positive correlation between life events and adolescent depression, attention should be paid to the influence of life events on adolescent depression in psychological counseling and interventions, and importance should be placed on mental health education and students’ ability to handle life events in a positive way. Moreover, the influence of specific life events on individuals of different ages and in different gender groups should be noted.

The limitations and prospects of this research are as follows: (1) Meta-analysis is a statistical method that is highly dependent on the completeness of the literature search. It is difficult to locate all relevant studies for one meta-analysis. In this meta-analysis, we excluded articles that did not include correlation coefficients for life events and adolescent depression. As such, some samples were lost. (2) Not all potential research fields were incorporated in this meta-analysis. For example, the present study did not address whether the use of different questionnaires influences the observed relationship between life events and adolescent depression. Besides, future studies should place more emphasis on the effects of life events on specific aspects of adolescent depression so that targeted intervention measures can be taken. The internal mechanisms of the influence of life events on adolescent depression should also be explored. The cognitive vulnerability-stress theory states that individuals with certain cognitive tendencies will explain stressful events to themselves in a way that increases the incidence of depression [122]. According to pressure forming theory, individuals under external or social pressure will perform a series of actions, some of which will induce negative life events and cause depression [123-127]. (3) Studies that examined the moderating role of gender and type of life events were limited, which may have led to bias in the analysis results. To reach more definitive conclusions, more empirical support and a larger sample size are required [128- 136]. (4) A significant disparity was discovered when cultural background was used as a moderating variable. Classification of cultural background in this study is general because the discussions were confined to Chinese (serving as a representative of Eastern culture) and Western cultural backgrounds. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct more comparative studies that include other cultures.

Conclusions

The findings of our meta-analysis of studies conducted over the last decade are as follows.

(1) There is a significant positive correlation between life events and depression in adolescents, with an effect size of 0.319.

(2) Gender affects the relationship between adolescent life events and depression. Specifically, the relationship is greater in females.

(3) Cultural background affects the relationship between life events and depression in adolescents. Specifically, this relationship is greater for individuals from Eastern culture.

(4) The type of life event affects the relationship between life events and depression. Trivial affairs are more closely related to depression in adolescents. The mode in which life events are measured does not affect the observed relationship between life events and adolescent depression. That is, no significant discrepancies exist between studies that measured both the frequency and juveniles’ subjective feelings about life events of life events and those that measured frequency alone.

References

- Liao Quanming,XieYulan (2007) Study of impoverished students’ life events, coping strategies and mental health. Journal of Chongqing University of Science and Technology: Social Science Edition.

- Pengli H, Zhongming Z, Yuanyuan Y, Xiaowei G (2013) Relationship between college students’ life events, sense of coherence and depression. China Journal of Health Psychology 20: 1722-1724.

- Boardman JD, Alexander KB, Stallings MC (2011) Stressful life events and depression among adolescent twin pairs.Biodemography and social biology57: 53-66.

- Burton E, Stice E, Seeley JR (2004) A prospective test of the stress-buffering model of depression in adolescent girls: no support once again. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology72: 689.

- VeytiaLópez M, González ArratiaLópez Fuentes NI, Andrade Palos P, Oudhof H (2012) Depresión en adolescentes: El papel de los sucesos vitales estresantes.Salud mental35: 37-43.

- Fombonne E (1994) Increased rates of depression-updated of epidemiologic findings and analytical problems.ActaPsychiatrScand90: 145-156.

- Arnett JJ (2000) Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teen through the twenties. American Psychologist 55: 469-480.

- Steinberg L, Cauffman E (1999) Developmental Perspective on Serious Juvenile Crime: When Should Juveniles Be Treated as Adults, A.Fed. Probation63: 52.

- Fox JK, Halpern LF, Ryan JL, Lowe KA (2010) Stressful life events and the tripartite model: Relations to anxiety and depression in adolescent females.Journal of adolescence33: 43-54.

- Wadsworth ME, Raviv T, Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK (2005) Parent and adolescent responses to povertyrelated stress: Tests of mediated and moderated coping models.J Child Fam Stud14: 283-298.

- Lazarus RS,Folkman S (1984) Stress.Appraisal and coping.

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH (1967) Life crisis and disease-onset-I. Qualitative and quantitative definition of life events composing life crisis.Unpublished manuscript, Navy Neuropsychiatric Research Unit, San Diego, CA.

- Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, Lazarus RS (1981) Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events.Journal of behavioral medicine4: 1-39.

- Desen Y, Yalin Z (1990) Life Events Scale. Behavioral Medicine.

- Liyun F, ZuoyongW (2000) Investigation of adolescents’ life events. Henan Journal of Preventive Medicine 11: 21-24.

- Shijie J (2000) Study of the relationship between the stress intensity of junior high school students’ daily events and mental health. Youth Studies.

- Goldberger L, Breznitz S (2010)Handbook of stress. Simon and Schuster.

- Yanping Z, Desen Y (1990) Investigation of life events in China - The Basic characteristics of stressful life events in normal people. Chinese Mental Health Journal 4: 262-267.

- Mingyuan Z (1993) Manual of psychiatric rating scale. Changsha: Hunan Science and Technology Press.

- Yuzhong W, Liyun F, Zhiming W, Kejun L, Guoqiang Z, et al. (1999) Preliminary preparation of junior college and secondary school students’ life events scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal 13: 206-207.

- Xianchen L, Xiangdong W, Xilin W (1999) Adolescent self-rating life events checklist. Chinese Mental Health Journal 1: 31-36.

- Chang EC,Sanna LJ (2003) Experience of life hassles and psychological adjustment among adolescents: does it make a difference if one is optimistic or pessimistic?.Personality and Individual Differences34: 867-879.

- Ma Weina, Xuhua (2006) The relationship among high school students’ life events, self-efficacy and depressive emotions. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 14: 303-305.

- Wang Jun, Jin Yuelong, Chen Yan, Yu Jiegen, He Lianping, Yao Yingshui (2013) Correlation analysis of medical college students’ depression and life events. ActaAcademiaeMedicinaeWannan 32: 151-153.

- Kercher AJ, Rapee RM, Schniering CA (2009) Neuroticism, life events and negative thoughts in the development of depression in adolescent girls.Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology37: 903-915.

- Gau JM, Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley JR (2012) Negative Life Events and Substance Use Moderate Cognitive Behavioral Adolescent Depression Prevention Intervention.Cognitive behaviour therapy41: 241-250.

- Shahar G, Priel B (2003) Active vulnerability, adolescent distress, and the mediating/suppressing role of life events.Personality and Individual Differences35: 199-218.

- Angold A (1988) Children and adolescent depression.2.research in clinical populations.British Journal of Psychiatry 153: 476-492.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000)Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR®. American Psychiatric Pub.

- Graber JA, Sontag L M (2004) Internalizing problems during adolescence.Handbook of adolescent psychology.

- Fengjin C (2003) Freshmen life events questionnaire:Freshmen’s coping strategies and mental state of life events and their influences on physical and mental health. Master’s thesis (Doctoral dissertation).

- Jisheng W, Bingwu Q, He Ershi (1997) Preparation and standardization of middle school students’ depression scale. Science of Social Psychology 45: 4-6.

- Yuejuan Z, Kele Y, Jinli W(2005) Path analysis of the influences of life events negative automatic thoughts and coping strategies on college students’ depression. Psychological Development and Education 1: 96-99.

- Li Li (2013) Family education style, life events and their relationships with adolescent depression(Master’s thesis, Anhui Medical University).

- Xiaohua L, Kaida J (2004) Summary of the relationship between life events and depression. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science 13: 347-348.

- Compas BE, Grant KE, Ey S (1994) Psychosocial stress and child and adolescent depression. InHandbook of depression in children and adolescents, Springer USA.

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY (2001) Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability–transactional stress theory.Psychological bulletin127: 773.

- Williamson DE, Birmaher B, Anderson BP, Al-Shabbout M, Ryan ND (1995) Stressful life events in depressed adolescents: the role of dependent events during the depressive episode.Journal of the American Academy of ChildAdolescent Psychiatry34: 591-598.

- Van Os J, Jones PB (1999) Early risk factors and adult person-environment relationships in affective disorder.Psychological Medicine29: 1055-1067.

- Yu Jie, Meiyu X, JiJianling, GuJianhui, Jianzhong Z,Ping W (2004) Correlation analysis of rural high school students’ depression, anxiety and stressors. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science 13: 68-69.

- XuBiyun, Bingwei C, Zongzan N,Xuezhu H (2004)Canonical correlation analysis of adolescent behavior, emotional problems and life events. Chinese Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 4: 263-266.

- Pingyan Z (2008) Literature review of domestic and foreign influencing factors of depression. Journal of Baoshan Teachers’ College 27: 36-40.

- Bidzi EJ (1984) Stress factors in affective diseases.The British Journal of Psychiatry144: 161-166.

- Billings AG, Cronkite RC, Moos RH (1983) Social-environmental factors in unipolar depression: comparisons of depressed patients and nondepressed controls.Journal of abnormal psychology92: 119.

- Brown GW, Bifulco A, Harris TO (1987) Life events, vulnerability and onset of depression: some refinements.The British Journal of Psychiatry150: 30-42.

- Hammen C, Marks T, Mayol A, DeMayo R (1985) Depressive self-schemas, life stress, and vulnerability to depression.Journal of Abnormal Psychology94: 308.

- HolahanC, MoosR (1991) Life stressors, personal and social resources,and depression: a4-year structural model. J AbnormPsychol100:31-38.

- Kendler KS, Kessler RC, Walters EE, MacLean C, Neale MC, et al. (1995) Stressful life events, genetic liability, and onset of an episode of major depression in women.Am J Psychiatry 152: 833-842.

- Patrick V, Dunner DL,Fieve RR (1978) Life events and primary affective illness.ActaPsychiatricaScandinavica58: 48-55.

- Paykel ES (1979) Recent life events in the development of the depressive disorders.The psychobiology of the depressive disorders: Implications for the effects of stress.

- Shrout PE, Link BG, Dohrenwend BP, Skodol AE, Stueve A, Mirotznik J (1989) Characterizing life events as risk factors for depression: the role of fateful loss events.Journal of Abnormal Psychology98: 460.

- Tingting Z (2006) Influences of life events and coping strategies on college students’ negative emotions. Master’s thesis of Northeast Normal University.

- O'Neill SC, Cohen LH, Tolpin LH,Gunthert KC (2004) Affective reactivity to daily interpersonal stressors as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms.Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology23: 172-194.

- Hoeksema SN (1990)Sex differences in depression. Stanford University Press.

- Kessler RC, Walters EE (1998) Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the national comorbidity survey.Depression and anxiety7: 3-14.

- López MV, Fuentes NIGAL, Palos PA,Oudhof H (2012) Depression in adolescents: The role of stressful life events.Salud Mental35: 33-38.

- Sherrill JT, Anderson B, Frank E, Reynolds CF, Tu XM, Patterson D, Kupfer DJ (1997) Is life stress more likely to provoke depressive episodes in women than in men?.Depression and Anxiety6: 95-105.

- Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG, Mazure, CM (2001) Sex differences in event-related risk for major depression.Psychological medicine31: 593-604.

- Kendler KS, Thornton LM, Prescott CA (2001) Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects.Am J Psychiatry158: 587-593.

- Kagitçibasi Ç (1996) Family and human development across cultures: A view from the other side.Psychology Press.

- Monroe SM, Simons AD (1991) Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders.Psychological bulletin.

- Windle M, Windle RC (1996) Coping strategies, drinking motives, and stressful life events among middle adolescents: Associations with emotional and behavioral problems and with academic functioning.Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

- Kanner AD, Feldman SS, Weinberger, DA, Ford ME (1987) Uplifts, hassles, and adaptational outcomes in early adolescents.The journal of early adolescence7: 371-394.

- Rowlison RT,Felner RD (1988) Major life events, hassles, and adaptation in adolescence: confounding in the conceptualization and measurement of life stress and adjustment revisited.Journal of personality and social psychology.

- Li Yongxin, Gugangya Z (2007) A cross-lagged analysis of college students’ life events and depression. Chinese Journal of School Health 28: 28-29.

- Yang Li (2008) Study of the relationship among perfectionism, stress, response, social supports and depression. Doctoral dissertation. Tianjin Normal University.

- Yimei W,Jian Z (2009) Relationship among college students’ life events, cognitive emotion regulation and depression. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 16: 582-583.

- He Shexin (2009) Study of the relationship between senior high school students’ life events, social supports, coping strategies and depression [D](Doctoral dissertation, Changsha: Hunan Normal University).

- Hu Pengli, Zhongming Z, Yuanyuan Y, Xiaowei G(2013) Relationship between college students’ life events, sense of coherence and depression. China Journal of HealthPsychology 20: 1722-1724.

- Li Peng (2012) Study of junior high school students’ life events, mental resilience and their relationships with mental health(Master’s thesis, Harbin Normal University).

- Flynn M, Rudolph KD (2011) Stress generation and adolescent depression: contribution of interpersonal stress responses.Journal of abnormal child psychology39: 1187-1198.

- Yang Juan (2010)The regulating role of senior high school students’ rumination on the relationship between life events and depression or anxiety symptoms - multi-period tracking study (Doctoral dissertation, Central South University).

- Xiumei C (2006) Study of junior high school students’ depression and its correlation factors (Master’s thesis, Hebei Normal University).

- Fang W (2012) Influences of high school students’ life events and self-esteem on depression. Shaanxi Education: Higher Education Edition12: 13-14.

- Hui C, Huihua D, Ping Z, Zongbao L, Guangzhen Z, Zuhong L (2012) Relationship between depression and life events in early adolescents: A cross-lagged regression analysis. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 20: 80-83.

- Hammen C, Henry R,Daley SE (2000) Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity.Journal of consulting and clinical psychology68: 782.

- Hammen C, Mayol A, DeMayo R, Marks T (1986) Initial symptom levels and the life-event–depression relationship.Journal of Abnormal Psychology95: 114.

- Post RM (1992) Transduction of Psychosocial Stress into the Neurobiology.Am J Psychiatry149: 999-1010.

- Huijuan D (2010) Study of the relationship between college students’ psychological pressure, coping strategies and mental health [D](Doctoral dissertation, Shenyang: Northeast Normal University).

- Shurong S, Baijun Z, Shuhua S, Xiulian T, Huidong W, et al.(2013) Correlation study of college students’ life events, coping strategies and mental health. Journal of Shanxi Finance and Economics University.

- Aiping S (2006) Analysis of vocational medical freshmen’s mental health and relevant factors [D]. Master’s thesis of Zhejiang University.

- Tafarodi RW, Smith AJ (2001) Individualism–collectivism and depressive sensitivity to life events: the case of Malaysian sojourners. International Journal of Intercultural Relations25: 73-88.

- Tan Erli, Chu Binlin, Yu Jiangping, Chen Qi, Lu Hongchun, et al. (2012) Multiple regression analysis of medical college students’ depression and its influencing factors. Journal of Qiqihar University of Medicine 32: 3519-3520.

- Nar T, Borge AIH, Fundingsrud HP, Christie HJ, Torgersen S (2004) The role of stressful life events in the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence - A longitudinal community study.Journal of Adolescence27: 153-163.

- Wang Lien, Wang Jisheng (2005) Correlation analysis of medical college students’ specific life events and depression. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation 9: 55-57.

- Xiuxi W, Yuhong G, Weijie L, Qiaoling X (2010) Effects of resilience and life events on the depression in vocational college students in Handan. Chinese Journal of School Health 31: 565-566.

- Qiaozhen X, Jing L, Jiuming X,GuihuaY (2009) Correlation analysis of high school graduates’ anxiety and depression. Sichuan Mental Health 22: 106-108.

- Costello DM, Swendsen J, Rose JS, Dierker LC (2008) Risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of depressed mood from adolescence to early adulthood.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology76: 173.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS (1994) The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence.Psychological bulletin.

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL (2008) A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression.Handbook of depression in children and adolescents.

- Lloyd C (1980) Life events and depressive disorder reviewed: II. Events as precipitating factors.Archives of General Psychiatry37: 541-548.

- McLaughlin KA,Hatzenbuehler ML (2009) Mechanisms linking stressful life events and mental health problems in a prospective, community-based sample of adolescents.Journal of Adolescent Health44: 153-160.

- Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K,Nolen-Hoeksema S (2013) Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults.Journal of abnormal psychology.

- Morrison R, O'Connor RC (2005) Predicting psychological distress in college students: The role of rumination and stress.Journal of Clinical Psychology61: 447-460.

- Natsuaki MN, Ge X, Brody GH, Simons RL, Gibbons FX,Cutrona CE (2007) African American children’s depressive symptoms: the prospective effects of neighborhood disorder, stressful life events, and parenting.American journal of community psychology39: 163-176.

- Oppedal B, Røysamb E (2004) Mental health, life stress and social support among young Norwegian adolescents with immigrant and host national background.Scandinavian Journal of Psychology45: 131-144.

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Posterino M, Carlin JB, Bowes G (2003) Life events and early onset depression: cause or consequence? Psychological medicine33: 1203-1210.

- Rood L, Roelofs J, Bögels SM,Meesters C (2012) Stress-reactive rumination, negative cognitive style, and stressors in relationship to depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth.J youth adolescence41: 414-425.

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M (2007) Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status.Development and psychopathology19: 497-521.

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM,Prescott CA (1999) Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression.Am J Psychiatry156: 837-841.

- Kraaij V, Garnefski N, de Wilde EJ, Dijkstra A, Gebhardt W, et al. (2003) Negative life events and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: Bonding and cognitive coping as vulnerability factors? J youth adolescence32: 185-193.

- Li Shaoming (2007) Relationship between female college students’ life events and depression. China Science and Technology Information 17: 126.

- Li Songying, Wen Nai (2006) Study of medical students’ anxiety, depression, loneliness and relevant factors. Zhejiang Journal of Preventive Medicine 18: 13-15.

- Li Yanhong (2003) Study of impoverished college students’ depressive symptoms and relevant factors. Health Psychology Journal 11: 27-28.

- Li Yi (2005) Study of female university students’ depression, life events and pressure handling (Doctoral dissertation, Master’s thesis of Hohai University.

- Yongxin L, Guangya Z (2006) Study of the relationship between stress, lassitude and depression. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 14: 472-474.

- Li Yuxia (2013) Adolescent depression, anxiety and relevant factors. China Journal of Health Psychology.

- Baoling L,YuemingG (2003) Correlation study of vocational medical students’ depression and life events. China Higher Medical Education.

- Jianan L, Xiaomei S, Jingjin, Yi Huanqiong, Junjuan L, Rongchun P, et al. (2003) Health prevention Study of female nursing students’ depression and relevant factors. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science.

- Ting L, Yijiang C,Huihua D (2013) Follow-up study of life events’ influences’ on male freshmen’s depression and anxiety. Journal of Jiangsu institute of Education: Social Science 29: 31-34.

- Chen Fuxia, Zhang Fujuan (2010) Reform school students’ life events and unhealthy emotions and their relationships with coping strategies. Chinese Journal of Special Education.

- Chen Hongmin, Zhao Lei, Liu Lixin (2009)Study of the relationship between college students’ negative life events and mental health. China Youth Study.

- Chen Yu, Xiaoyuan Z, Liu Xiaoqiu, Wei W (2005) Study of the relationship between nursing students’ life events and mental health. Chinese Journal of School Health 26: 630-631.

- Chengshu D (2010) Study of life-behind adolescents’ depression condition (Master’s thesis, Southwest University).

- Houcai D, Jingyuan Y, Bing D, Ping Y, Anxie T, et al. (2012) Relationship between middle school students’ psychosocial factors and depression. Chinese Journal of Public Health 28: 1274-1277.

- Dyson R,Renk K (2006) Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping.Journal of clinical psychology62: 1231-1244.

- Yuzhong W, Liyun F, Zhiming W, Kejun L, Guoqiang Z, et al. (1999) Preliminary preparation of junior college and secondary school students’ life events scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal 13: 206-207.

- Zhengzhi F (2002) Study of social-information processing ways of middle school students’ depressive symptoms: Doctoral dissertation.

- Broderick PC, Korteland C (2002) Coping style and depression in early adolescence: Relationships to gender, gender role, and implicit beliefs. Sex Roles46: 201-213.

- Peled M, Moretti MM (2007) Rumination on anger and sadness in adolescence: Fueling of fury and deepening of despair.Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology36: 66-75.

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Brook JS (2001) Emotional reactivity and risk for psychopathology among adolescents.CNS spectrums6: 27-35.

- Du Linzhi (2002) Cultural background and the differentiation of cognitive attribution(Doctoral dissertation, Tianjin: Nankai University).

- Fong VL (2006) Coming of age under China’s one-child policy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Chun CA, Moos RH, Cronkite RC (2006) Culture: A fundamental context for the stress and coping paradigm. InHandbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping, Springer USA.

- Rothbaum F,Pott M, Azuma H, Miyake K,Weisz J (2000)The development of close relationships in Japan and the United States: Paths of symbiotic harmony and generative tension.Child Development 71: 1121–1142.

- Dong Na (2012) Study of the differences between Chinese culture and western culture. Folk Art and Literature.

- Bingwu Q, Jisheng W (2000) Review of diathesis-stress theory in depression study. Psychological Science, 23 361-362.

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, et al. (1998) Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study.Journal of abnormal psychology.

- Hammen C (1991) Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression.Journal of abnormal psychology100: 555.

- Jianwei X, Si Guoxing (2005) Correlation study of senior high school students’ life events, mental health and subjective happiness. Journal of Hebei Normal University: Educational Science Edition 7: 75-78.

- Zhaoxia X, Luli, Zhiqun L (2010) Investigation of impoverished college students’ depressive emotions. China Journal of Health Psychology.

- Zhang Li, Liu Bo (2003) Investigation and analysis of nursing students’ depression condition. Journal of Nursing Science 18: 918-919.

- Wenyue Z (2011) Study of college students’ depression distribution and the effectiveness of early intervention (Master’s thesis, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine).

- Carolyn ZW, Bonnie KD, Slattery MJ (2000) Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: Prospects, pitfalls, and progress in understanding the development of anxiety and depression.Development and Psychopathology12: 443-466.

- Kehui Z, Jing X, Li Furong (2008) Relationship among college students’ coping strategies, depression and anxiety. Journal of Changsha Aeronautical Vocational and Technical College 7: 74-77.

- Bouma E, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Oldehinkel AJ (2008) Stressful life events and depressive problems in early adolescent boys and girls: the influence of parental depression, temperament and family environment.Journal of affective disorders105: 185-193.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences